In Shendi, craft is not merely a profession; it is a mirror reflecting memory across time and place. In the old alleys and among riverside palm groves, the patterns carved on wooden doors sit alongside stories of clay and mud. Women skillfully weave palm fronds into objects brimming with nostalgia for a time when mastery equaled dignity. In Shendi, the cradle of Sudanese handicrafts, clay is still kneaded as it has been for generations.

Large Pottery jars (Al-zeer) used to store drinking water. Source: Facebook

Local clay varieties, such as Al-bulti, al-zafouti, al-maqar, and al-gurair, are prized for their quality, often enhanced with the Nubian “Teryaq” recipe for increased durability. In Al-Kemair workshop north of Al-Matama, Ibrahim Ahmed Abdullah, a hereditary potter, works in a rhythm that oscillates between wisdom and silence. He shapes the clay, dries it under the sun, and fires it in traditional kilns fueled with wood and animal dung to regulate heat and ensure strength. Thus, craftsmanship in Shendi emerges as one of the purest expressions of traditional professionalism.

Household utensils made of pottery. Source: Facebook

Pottery there is more than household tools; it is cultural documentation: al-zeer narrates the story of water, the qulla preserves storage practices, and the jebana embodies hospitality rituals. In Darfur, women transform clay and reeds into art that astonishes. In the House of Jebana, coffee boils, yet shapes arise from the clay itself, adorned with patterns resonating like earth’s hymns. Colorful mandola mats for celebrations are more than decorative; they testify to the land’s struggles and communal belonging. In the Kass market, leather goods, pottery, and Markop daggers are on display for all to see, in an open display of craft memory.

The mandola is made in Kordofan and Darfur. Source: Darfur Revival Initiative Facebook page

In Kordofan, embroidered garments are not luxury, they are visual folk narratives, reflecting the symbolism of place, a mother’s emotions, and a bride’s longing for her village. Al-Qutiyya is inscribed with patience, turning walls into identity maps readable by sight and insight. Local textiles, mat weaving, and pottery travel through markets as songs do: with love and care.

In the East, the story is unique. Where desert meets sea, women craft silver and gemstone jewelry and embroider garments with symbols of the sea and sand. In Al-Beja houses, weaving, spinning, and jewelry-making secrets are passed down, adorning heads with necklaces that speak of origin, tribe, and deferred dreams. In Suakin’s ports, ancient trade influences merge with dagger engravings and embroidered leather, reflecting a migratory identity. Here, crafts are not mere consumption, they are acts of belonging.

Adroub's dagger. Source: Getty Images

Across Sudan, palm fronds are turned into wooden beds in Shendi, mats for infants in Darfur, and intricately sheathed daggers in the East. These women’s crafts are not random, they are systems of knowledge and social structures, transmitted through oral tradition, experimentation, observation, and communal practice. They are unwritten languages etched into walls, bodies, and the eyes of grandmothers.

But the pressing question remains:

Who will carry this heritage when the fire beneath the jebana fades?

Who will embroider Al-qutiyya when the grandmothers are gone?

Who will spin the sea into the East’s fabric?

And who will explain to the city that these hands once crafted a nation?

These questions confront the harsh reality that these crafts face, particularly visible in places like the Antique Market.

The Antique Market and the Secrets of Craft in the Heart of Omdurman

In the heart of Omdurman, where old alleys intersect with nostalgic memory, the Antique Market stands as a living archive of Sudanese crafts, resisting oblivion with ebony, leather, palm, and metal. The market is not merely a place to sell crafts; it is an open stage where the stories of time are presented through intricate carvings, traditional vessels, and models pulsing with local spirit. Bashir Ali Al-Khidr, a market spokesperson, emphasizes that these crafts are not luxuries for visitors but a living extension of collective memory, rooted in Sudanese culture and history. It is an alternative language spoken by hands when time falls silent.

Yet behind this scene lies a painful paradox: declining tourism, then conflict, destruction and economic pressure have turned this proud craft into a dream struggling to survive. The market faces stagnation, and artisans, who have long been the narrators of cities, sell their silence, awaiting customers who may never come.

A rug made of palm leaves. Source: Facebook

When Hands Engrave the Memory of Clay: Women Shaping Stories

Where clay meets water, women from the White Nile banks knead it with fingers as their grandmothers once kneaded bread in village mornings. They do more than make pots—they assert presence in a world determined to marginalize them. In villages such as Kajbar and Al-Qurair, women have been working with clay for centuries, guarding a heritage that passes from hand to hand, from kiln to kiln, unbroken.

Pottery is not merely a livelihood; it is resistance, leaving a mark on land threatened by climate change and economic neglect. When male-dominated pottery industries declined, women continued producing Al-qilal (Storage Jars), tagines (Cooking Pots), and al-barmat (Large Storage Pots), silently transmitting heritage while local markets were overtaken by imported glass and plastic.

In an interview published by “Women’s Literacy Sudan,” one craftswoman shared that she learned the trade from her mother. Though without formal education, she has intimate knowledge of clay, drying, and firing techniques. During peak seasons, women sleep near kilns to keep the fire alive, as if guarding an entire way of life. With scarce resources and rising raw material costs, they innovate, recycling broken clay, sharing materials cooperatively, and forming small solidarity networks that redefine leadership beyond air-conditioned offices and presentation halls.

Coffee pots made of pottery. Source: Getty Images

When Heritage Suffocates: Who Will Survive?

Amid digital and economic transformations, local reports indicate that approximately 40% of Sudanese handicrafts are now at risk of extinction. The crisis is not limited to the market; it extends to the collapse of narratives that once gave artisans their status, products their meaning, and skills their dignity. Despite their deep-rooted tradition, these crafts struggle to find a foothold in an economy dictated by supply-and-demand algorithms. Documentation is scarce, competitive design is limited, and digital marketing is insufficient to make them thrive on modern commerce platforms.

Nevertheless, some rescue efforts have emerged: Facebook pages showcasing products and youth initiatives documenting the stories behind them. Yet these remain largely individual endeavors, unable to effect lasting change without institutional support that bridges heritage and creativity, economy and culture.

Women and Handicrafts: Economic and Cultural Power

In Darfur and displacement areas, handicrafts are among the most vital means of survival for women. Accurate data is limited, but partial studies indicate that crafts account for roughly 5% of women’s economic activity in camps. It is not a luxury, it is an act of survival. Recognizing women’s crafts as economic and knowledge tools is key to transforming fragility into strength rather than mere replacement.

(Al-Tabaq) is made of palm leaves and is used to cover food in Kordofan and Darfur. Source: Flicker

Between Antiquity and Modernity: The Future of Sudanese Crafts

Handicrafts do not need pity, they need partnership: between artisan and designer, product and technologist, memory and future. This is a battle for meaning, not just for the market. Preserving crafts safeguards not only skills but also historical and spiritual codes that cannot be imported from China or Turkey.

Thus, appreciating the beauty of craft is not enough; conscious and deliberate action is required:

- Creating digital platforms that promote artisans and document their stories.

- Developing training programs that respect the uniqueness of regions and local communities.

- Launching audiovisual documentation campaigns that retell these stories anew.

Handicrafts are more than skills, they are a cultural project. If we do not champion them, who will?

When Necessity Becomes Narrative: Why Do Some Crafts Endure While Others Fade?

One might assume that the disappearance of handicrafts is simply a matter of time or technological progress. Yet the truth is far more complex and deeply human. Take, for example, the dagger carried by the Adaroubi man: it is not merely an old piece of metal or a beautiful cultural relic. It is part of identity, a daily tool for protection, and a silent language expressing strength and belonging. It has survived, handcrafted to this day, because the need for it has never vanished.

But what about the mashlaib? This exquisite palm-frond item once preserved food before the invention of refrigerators. Today, it is no longer necessary. As need disappeared, so did the craft. It remains only among heritage enthusiasts, hobbyists, or those seeking a decorative touch for their homes. This shifts the real question from:

"Is this craft old?"

to:

"Do people still need the product of this craft in their daily lives?"

Necessity is what gives craft life. It is what protects it from drowning into oblivion.

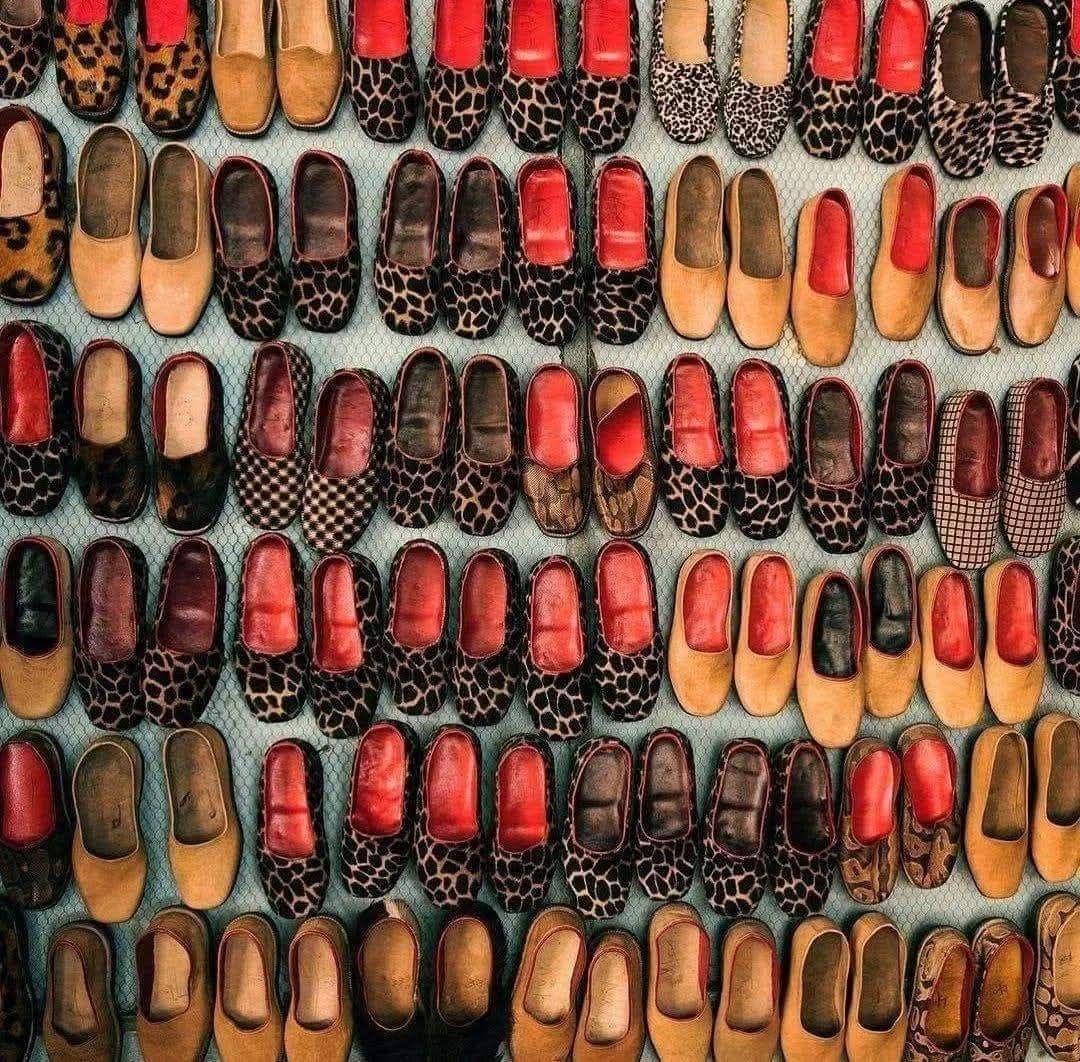

Al-Markoub (hand-made leather shoes). Source: X

The analogy is like ancient farming: if the land is sown to feed, it is essential; if it is cultivated merely for display or to preserve lineage, it becomes luxury or tradition maintained by a few. Crafts follow the same path—they oscillate between being a means of livelihood and becoming a small museum tucked in the corner of society. If unused, they gradually become part of “cultural luxury” or “visual nostalgia,” while life moves on. Look, for instance, at women in Darfur camps: they practice crafts because they need them to survive. Thread and needle, mats and palm fronds—they are not for decoration but for survival. Here, craft transforms from a sideline activity into a tool for endurance and rescue. Economy, then, is not just a factor of decline but also a reason for existence.

Crafts Are Not Relics… They Are Glimpses of the Future, Embodying Humanity

In a time when authenticity slips from our fingers, crafts are no longer mere traditional skills—they are living statements of the human relationship with the environment, collective memory telling the story of a nation, and the dignity of the hand. Sudanese handicrafts are not remnants of the past; they are rare signals of what the future could be: more humane, less consumerist, and closer to the earth.

Instead of mourning their disappearance, we should give them a chance to survive—not out of pity, but out of awareness. We must integrate them into digital markets, tell their stories, and grant them the confidence of the modern age, not crumbs of attention. Perhaps we do not need a revolution, but a simple decision: to buy consciously, to speak of crafts as we speak of ourselves, and to reorder our priorities so that the hand that creates becomes a partner to the hand that presses the button. Perhaps… change begins with the simplest act: choosing, one day, an item made with passion, not by a machine.