Warning and Disclaimer: The content you are about to read contains graphic and sensitive experiences. We advise the reader to exercise discretion and free choice. Read our full editorial notice here.

Forced marriage is any marriage that takes place without the full and free consent of one or both parties, and when one or both parties do not have the ability to end the marriage or separate, due to reasons including coercion or intense social and family pressure.

Child marriage becomes widespread during times of war due to the belief that parents are protecting their daughters from rape and preserving their honor.

According to the Sudan report issued in April 2024 by the European Union Asylum Agency, cases of forced marriage of girls and women to members of the Rapid Support Forces are increasing, with some cases involving fathers handing over their daughters under threat.

Every year, 15 million girls are locked away from a better life. Source: CAMFED.org

Statistics

Official statistics on early marriage in Sudan, a form of forced marriage that often occurs without the girl’s free and informed consent, date back to before the war. UNICEF data indicates that 1.9 million girls were married before the age of 15, representing 12%, and 5.1 million before the age of 18, representing 34%.

Following the outbreak of war in April 2023, reports recorded a significant increase in forced marriages due to poverty, displacement, and the collapse of services. The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) noted the prevalence of early marriage as a means of survival during the crisis. Islamic Relief reported that 93% of families lost their sources of income, which drove them to marry off their daughters.

The European Union Asylum Agency documented the expansion of early marriage as a means to protect girls from sexual violence. While no up-to-date precise figures are available, qualitative indicators confirm the worsening of the phenomenon since the war.

According to the Commission of Inquiry into Crimes and Violations of National and International Humanitarian Law, 1,392 cases of sexual violence, gang rape, and forced marriage were recorded. However, specialists believe these represent less than 2% of the actual number of violations, suggesting the true number of forced marriages and related abuses could exceed 69,000 cases, largely due to victims refraining from reporting out of fear of social stigma.

According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, the country has witnessed a 280% increase in the number of survivors seeking gender-based violence services.

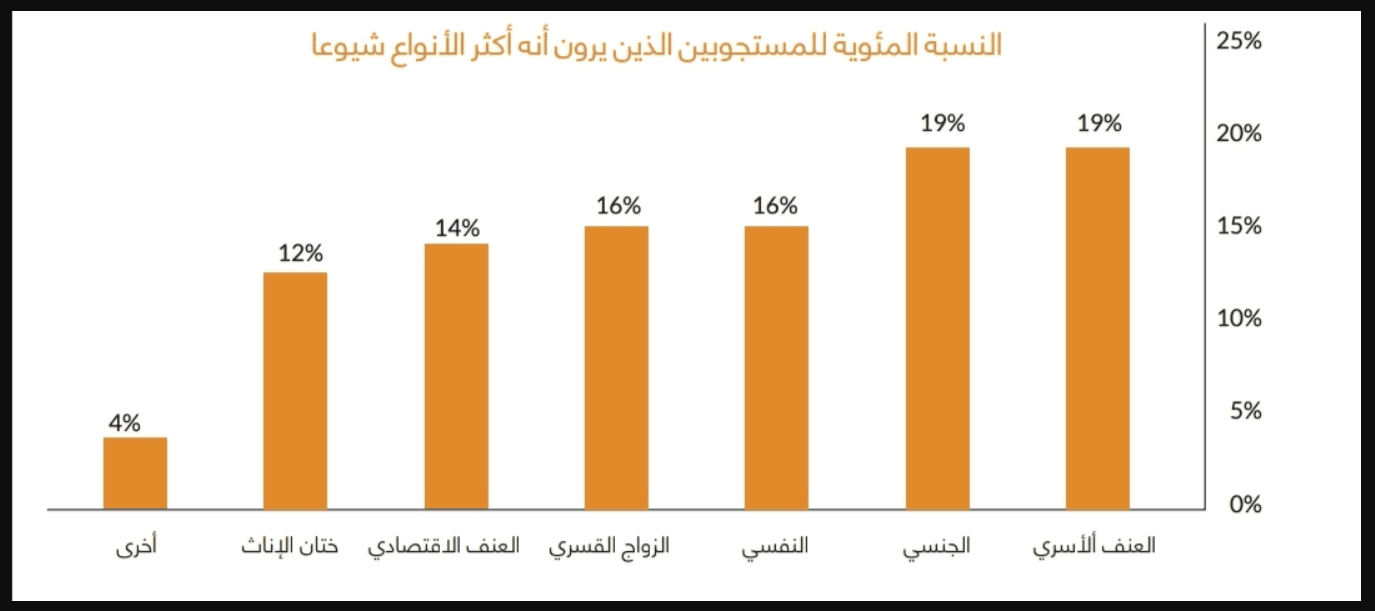

Forced marriage is one of the most common forms of gender-based violence, based on frequency analysis 2014, source: UNICEF

Control First, Followed by Forced Marriage

After invading any area, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) establish their military presence and then compel women and girls into forced marriage. Reports from Darfur, Khartoum, and Al-Gazirah reveal a systematic, not individual, pattern of marriage imposed under threat, with dowries often paid collectively by multiple fighters.

These marriages are not social unions; they are weapons used by fighters to entrench their coercive control and turn women’s bodies into tools for reshaping communities from within. This is organized sexual violence, veiled in the language of honor, but at its core, it is a form of slavery.

Legalizing Rape

In a village in North Kordofan State, Mona (who asked to keep her real identity private), a 17-year-old girl, survived an act of abuse disguised as marriage. The story began when a member of the RSF followed her home from the market and demanded that her mother marry her off to him. The mother, who lived in a small house with Mona and three other children, feared the soldier’s brutality and agreed to the marriage, afraid that her daughter might be raped.

After the marriage contract was signed, Mona discovered a shocking truth: two other members of the Rapid Support Forces had contributed to the dowry payment. One of them told her bluntly, “The three of us married you.” Stunned, Mona realized she was nothing more than the victim of a rape masked by false legality.

Mona asked to go to her room for a moment, then slipped out through the back door and told her mother what had happened. Acting quickly, her mother hid her daughter with neighbors. When a soldier returned looking for her, the mother denied seeing her, burst into tears, and threatened to report him to the area commander that he had killed or kidnapped her daughter. The mother gathered her children, including Mona, and left the village for a relatively safe area.

Caught Between Protective Intentions and Inevitable Realities

Khansaa (a pseudonym), a 21-year-old girl, was studying at the University of Khartoum. Her parents were both well-known teachers in their neighborhood. After the family fled Khartoum to Sennar, her father forced her into a marriage of coercion with her father’s much older friend, fearing she might be kidnapped or subjected to sexual violence by the Rapid Support Forces deployed in the area. Khansaa's mother says, “We married her off to protect her from the RSF, even if it was against her will.”

Forced marriage is based on coercion. Source: Okaz newspaper

Legal Silence, Human Cost

Forced marriage is not new in Sudan; it has roots dating back to peacetime, which helps explain the social and official leniency toward it during times of war. While international law criminalizes this type of marriage and classifies it as a war crime, Sudanese law remains incapable of preventing it or holding perpetrators accountable. Article 34 of the 1991 Personal Status Law requires a woman’s consent to marry, but it allows a guardian to conclude the marriage contract and obtain her approval afterward. A woman’s refusal is not considered sufficient to annul the marriage.

Although there are many international agreements, such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), that require full and free consent from both parties for a marriage to be valid, crimes related to forced marriage are still not recognized as standalone crimes under international humanitarian law. In most cases, these crimes are grouped under broader categories like inhumane acts, which complicates accountability and distances victims from the path to justice.

At the local level, many conflict-affected countries—such as Sudan and Yemen—lack legislation that sets a strict minimum age for marriage or explicitly criminalizes forced marriage. In Sudan, the law does not establish a clear legal minimum age for marriage and allows girls to be married as young as ten. This creates a wide legal opening for forced marriage to be treated as a lawful practice, even though it is, at its core, a crime against childhood and human dignity.

An image illustrating that law is failing the little girls. Source: Bara'a Mohamed

Forced Marriage in Conflict-Affected Arab Countries

In Syria, armed groups have committed grave violations by forcibly marrying off girls under the guise of protection, and forcibly transferring them to areas under their control, where they were subjected to being sold, gifted, or forced into marriage.

In Iraq, ISIS used forced marriage as a weapon of war, kidnapping girls and imposing marriage to its fighters, with documented cases of them being sold in online markets.

In Yemen, the absence of a law defining a minimum age for marriage has led to the widespread occurrence of forced marriage, especially in conflict-affected areas. Armed groups have exploited poverty and the legal vacuum to marry off girls without their consent.

Supporting Victims is a Priority

In the midst of war and collapse, women and girls who fall victim to forced marriage are left to face profound trauma and devastating physical and psychological consequences alone. Therefore, providing psychosocial support must be a top priority for humanitarian actors. Assistance should not be limited to shelter and medical care, but must also include psychological recovery, legal support, and access to humane and safe options for women who have been forcibly impregnated.

Organizations such as Plan International and Together Against Rape and Sexual Violence have shed light on the dangers of forced marriage and provided various forms of support to victims despite existing restrictions. However, there remains an urgent need to expand these initiatives and ensure that aid reaches those in need without military or bureaucratic obstacles.

Ultimately, many displaced families—or those living in areas occupied by the Rapid Support Forces or under direct threat of attack—resort to forced marriage as a last attempt to protect their daughters from violence, rape, or social stigma. Yet this choice does not offer real safety; instead, it deepens the suffering of girls and turns their bodies into another battlefield of abuse.

Forced marriage during wartime is nothing less than a continuation of systematic violence. Addressing it requires coordinated efforts from both the international community and local actors—through firm legislation, psychosocial and legal support, and the protection of women’s and children’s rights—so that girls and women are no longer held hostage to brutal circumstances or used as tools in ongoing conflicts.