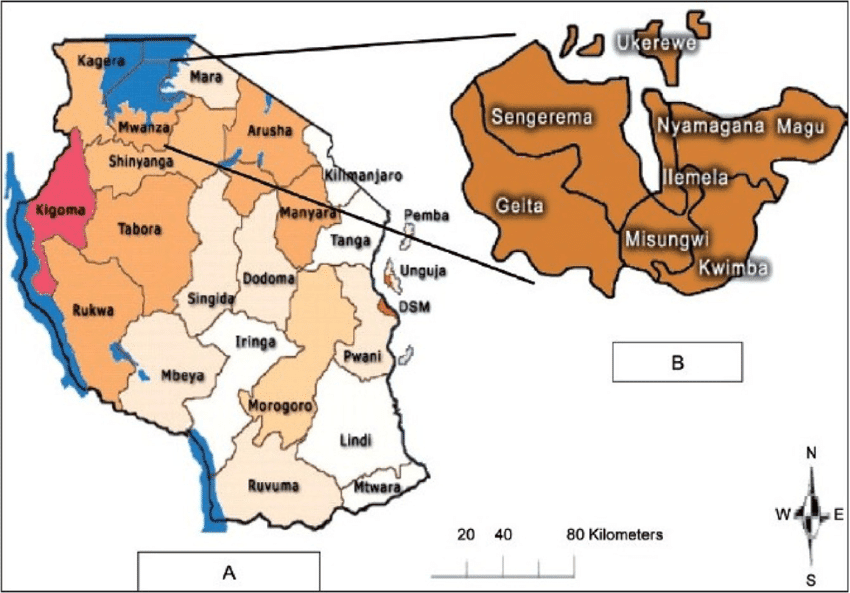

Mwanza Region hosts one of Tanzania’s fastest-growing youth populations. The 2022 National Population and Housing Census recorded 3.66 million residents, with about 38% aged 10–24. This population faces serious risks: adolescent fertility stands at 139 births per 1,000 girls aged 15–19; above the national average of 112.

Only 41.5% of 15–19-year-old girls in Mwanza have comprehensive HIV-prevention knowledge. Modern contraceptive use among sexually active adolescents remains low. The Tanzania HIV Impact Survey (THIS 2022–2023) found HIV prevalence among 15–24-year-olds in parts of Mwanza above the national average.

Map of Tanzania highlighting Mwanza Region, the setting of the project’s activities. Image by Mazigo-HD-Okumu, sourced online.

These patterns are most pronounced in communities like Kisesa, where the Kisesa HDSS research area has documented adolescent pregnancy rates exceeding 25% before age 19, low access to youth-friendly services, and silence around sexual health.

Tanzania’s National Adolescent Health and Development Strategy calls for rights-based, gender-sensitive approaches that reach adolescents where they already are. The National Multisectoral Strategic Framework on HIV/AIDS (NMSF V 2021-2026) identifies Mwanza as a priority region requiring stronger youth engagement and community-driven change.

This is the context in which the AICT Bujora Child and Youth Development Center operates at Kisesa ward. The center belongs to the Africa Inland Church of Tanzania, Diocese of Mwanza, and is registered under Compassion International Tanzania, one of more than 500 centers supported nationwide. Staff at the center witnessed the same realities reflected in national surveys: students fearful to ask sexual-health questions, parents unsure how to guide their children, and community leaders asking for help.

Before The Project: Evelyne’s World of Unasked Questions

Before the project began, Evelyne (19) was often felt caught between curiosity and silence. In school, sexual-health lessons were brief and rarely encouraged discussion. Teachers feared backlash. Students feared judgment. At home, the topic was considered inappropriate. Many Mwanza families expect such matters to remain private until marriage.

Evelyne, like many others, relied on friends, hearsay, and the internet; sources that often misled rather than informed. Her story became the human anchor for a challenge designed to open doors that had long remained closed.

Evelyne poses for a portrait during Demo Day, minutes before performing her song Jilinde, Wewe ni Taifa la Kesho for the community. Photo by Evelyne, AICT Bujora.

“I had limited knowledge about sexual and reproductive health rights, which left me vulnerable,” Evelyne recalls. ِAdding, “I wanted to learn, but there was nowhere safe to ask.”

The Project: Teaching First, Then Creating

The center decided to replace silence with sound, and stigma with color. Through the Kijana Jitambue Sasa Challenge; Swahili for “Youth, Know Yourself Now”, young people became messengers, using art and music to reshape how their communities talked about sexual health.

The "Kijana Jitambue Sasa" logo features a young man and woman united in singing; their forms filled with vibrant African prints. It visually declares the project's mission: using culturally-rooted creativity to amplify youth voices on health issues.

The project began months before the boot-camp. The team travelled to primary schools, secondary schools, colleges, and youth centers across the Mwanza Cluster to introduce clear, practical lessons on sexual health. They reached 1,495 students in schools such as Kisesa, Muungano, Wita, Kitumba, and Rumve, as well as students from Kolandoto and City Colleges of Health and the Institute of Rural Development Planning.

Speaking to pupils at Kisesa Primary School in a tailored session on self-awareness and respect. Photo by Philipo Florian.

Each session covered consent, protection, relationships, body changes, and where to seek help. The aim was simple: create a safe space where young people could hear accurate information and ask questions without fear or judgment. At the end of every session, students received brochures summarizing the discussion and were invited to take part in auditions for the creative challenge.

Dr. Ezekiel Matabalo leading an SRHR session at City College of Health and Allied Sciences. Photo by Philipo Florian.

This “learn first, create later” approach helped students understand the material before expressing it through music or art. It ensured that anyone who chose to join the challenge did so from a place of knowledge; not guesswork, a foundation that shaped the honesty and impact of the work that followed.

This model offers a clear lesson for others: when education is paired with expression, it becomes easier for young people to absorb, remember, and share. Any youth program; with or without advanced resources, can adapt the formula. Start with accurate information. Create a safe space. Invite young people to express what they learn in ways that feel natural to them. Their own voices then carry the message further than any lecture might.

A student at Lumve Secondary School in Kisesa shares her perspective on sexual and reproductive health and rights during an open forum. Photo by Philipo Florian.

The Auditions: A Journey Toward Leadership

The first round of auditions combined creativity with learning. Health professionals joined the sessions to repeat key messages and answer questions that students had been afraid to ask elsewhere. More than a hundred youth stepped forward. From that group, 150 were selected for the next stage based on their interest, originality, and understanding of the messages.

Judges listen to participants during the audition round at AICT Bujora, where creativity and understanding of SRHR themes were both assessed. Photo by Philipo Florian.

The second audition narrowed the group to 50. At this stage, the team looked not only for talent in singing or drawing but for young people who showed curiosity, confidence, and a desire to influence others. The final round identified 15 participants: 10 singers and 5 visual artists. Out of them, 13 made it to the boot-camp.

A participant sings her audition piece with full emotion as judges look on. Photo by Philipo Florian, AICT Bujora.

The Seven Day Bootcamp: Where Transformation Began

The seven-day bootcamp became the heart of the project. It gathered these young artists, singers, and storytellers in one space and guided them through an intense program of learning and creation. They revisited SRHR lessons with health experts, explored how to turn personal experiences into messages, practiced songwriting and studio recording, and worked with mentors to shape their artistic voice. The camp taught them how to communicate difficult topics with honesty and responsibility. By the end of the week, they were youth advocates equipped with accurate knowledge and creative tools strong enough to reach their peers and communities.

The Creative Outputs: Art That Speaks with Courage

The creative work that came out of the bootcamp carried more than rhythm and color. The young artists produced 11 original songs and 4 music videos, each shaped by conversations about consent, respect, and responsibility. Instead of lecturing, mentors asked participants to draw from real moments in their own lives; questions they had, pressures they faced, and confusing situations they had seen among friends. This helped the artists frame sensitive topics in language their peers would understand.

Evelyne (center) recording vocals for a theme song, “Kijana Jitambue Sasa Challenge,” a youth-led art and music project promoting sexual health awareness. Photo by Peter Salawe, AICT Bujora Center.

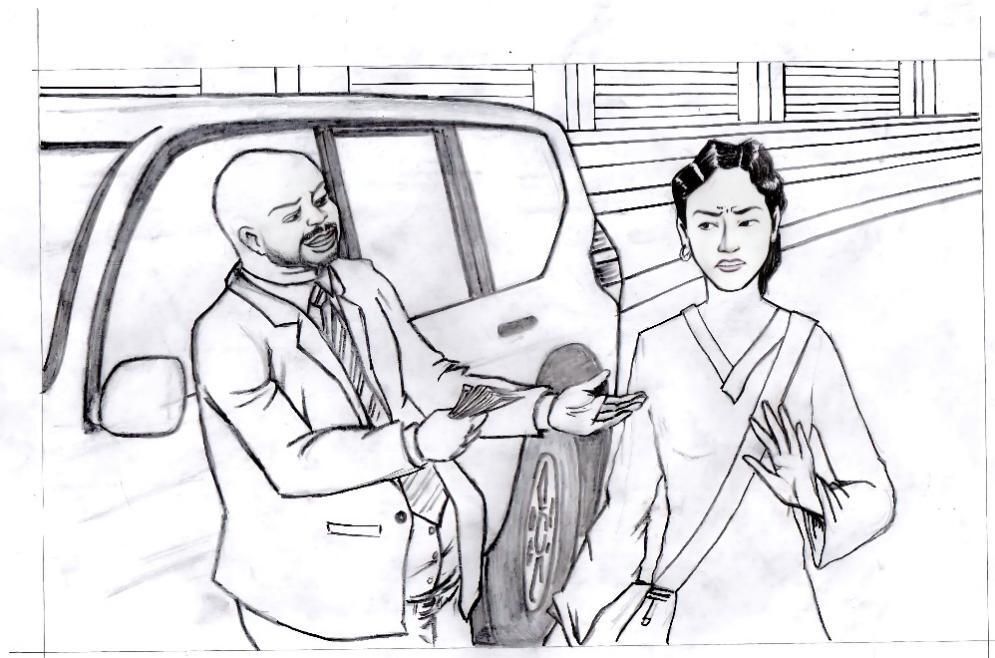

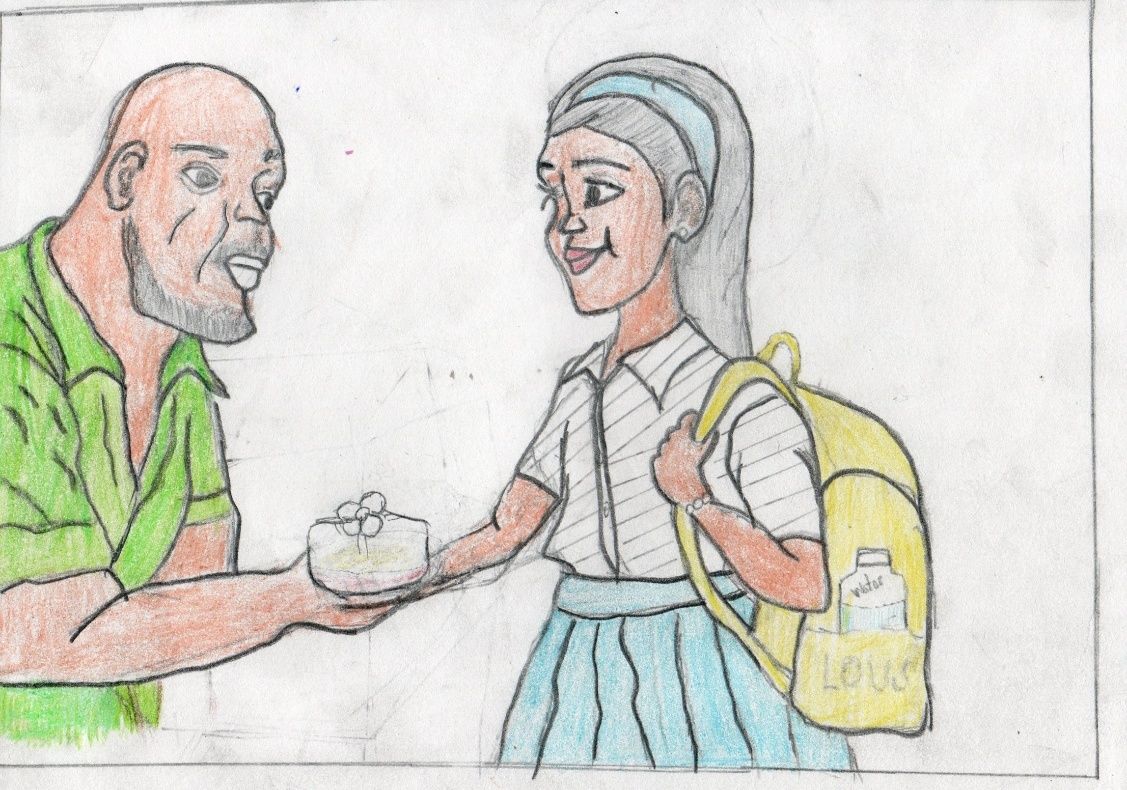

Adolescents often worry about crossing lines when talking about sexual health, but the project created space for them to set those boundaries themselves. Health experts guided them through what to include, what to avoid, and how to talk about protection and rights without shaming or sensationalizing the subject. The result was a set of songs that felt honest and respectful. One track, Heshima, encouraged youth to protect their dignity and avoid choices that risk their goals and future, another spoke about early relationships from the perspective of a girl warning her younger sister. The videos used simple scenes; friends talking under a tree, a student turning down pressure from an older partner, a youth visiting a clinic, to reinforce messages without exposing anyone’s privacy.

Youth participants record music on sexual and reproductive health rights and responsibilities during Kijana Jitambue Sasa Project, Mwanza, Tanzania. Photo by Peter Salawe, AICT Bujora Center.

What made this work powerful was afterwards, how quickly the messages spread. The songs played in school assemblies, on local PA systems, and through the phones of students who shared them with friends. For many young listeners, this was the first time they heard their own peers talk openly about topics adults usually avoid. The creative outputs opened doors for discussions teachers and parents had struggled to start.

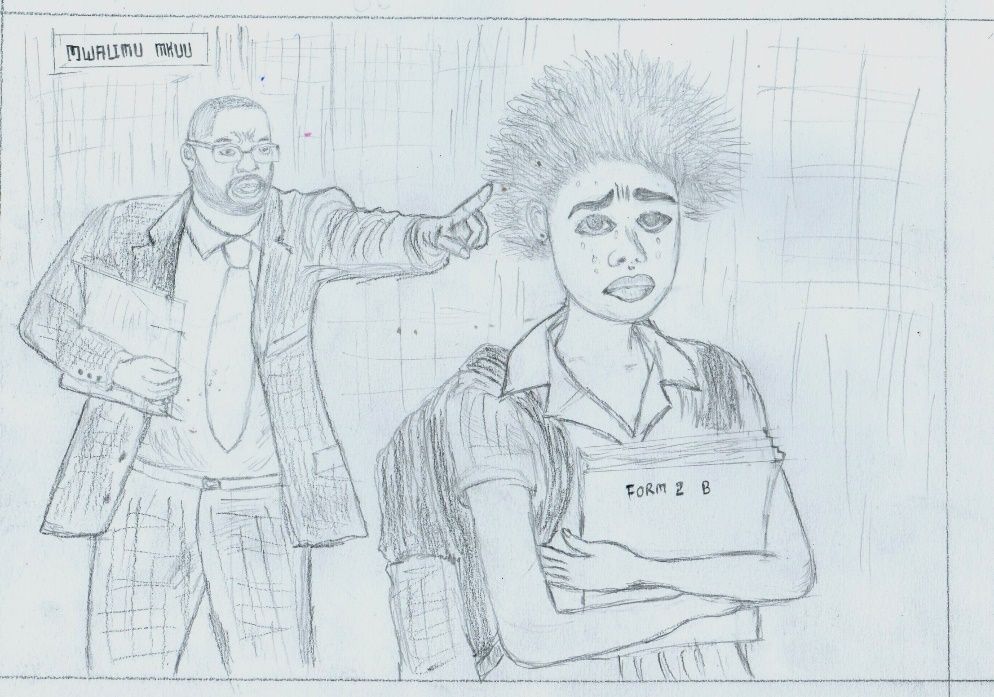

The visual artists brought a different kind of boldness to the project. They produced 20 artworks, each drawn from situations they had witnessed or struggled to understand.

Under the guidance of the author as an art instructor, young artists learn to channel their SRHR knowledge into powerful paintings and drawings. Photo by Peter Salawe, AICT Bujora Center

Their sketches showed girls navigating pressure from older partners, boys confronting misinformation from peers, and young people choosing to visit clinics for the first time. These images mirrored the realities many adolescents live with but rarely speak about.

A painting urging women to attend health clinics on time, part of the awareness artworks produced during the challenge. Drawing by Ammuly Ramadhan, AICT Bujora Center

A painting urging women to attend health clinics on time, part of the awareness artworks produced during the challenge. Drawing by Ammuly Ramadhan, AICT Bujora Center

Artwork depicting a man attempting to lure a young girl with money; highlighting economic vulnerability and the need for awareness. Drawing by Ammuly Ramadhan, AICT Bujora Center.

During the feedback sessions, health experts sat with the young artists to discuss framing. The goal was to encourage honesty while keeping dignity and respect at the center. The artists learned how to translate sensitive themes such as coercion, early pregnancy, unsafe relationships, into visuals that sparked reflection rather than fear.

To carry the messages into the community, the artworks were printed on 120 traditional kikoi headscarves and 50 fabric bags. This decision was intentional. Kikoi are worn in markets, churches, bus stands, and family gatherings. By placing the drawings on items people use every day, the project turned private concerns into public conversations; quietly, respectfully, and without confrontation.

A project social worker showcases bags printed with SRHR artwork. This design, with the Swahili caption "Elimu Sahihi, Vyanzo Sahihi" ("The Correct Sources, Credible Information"), depicts a doctor counseling a youth. Photo by Peter Salawe, AICT Bujora Center.

The response surprised even the team. Women wore the kikoi to events and asked about the messages. Students used the bags at school, prompting classmates to ask what the drawings meant. A few parents approached the center to say the images helped them start long-delayed conversations at home. The artwork became a moving classroom.

The Impact by Numbers and Stories

When the music stopped and the brushes dried, the numbers revealed how much had shifted. Before the project, only 42% of participating adolescents could correctly answer basic questions about consent, HIV prevention, and sexual-health rights. By the end of the program, that figure rose to 84%. Confidence in speaking about SRHR topics also increased sharply: only 3 out of 10 felt comfortable discussing these issues at the start, compared to 8 out of 10 after the bootcamp and outreach sessions.

These results were drawn from the project’s internal pre- and post-intervention surveys, conducted across the schools and centers that took part. The project’s creative outputs; songs produced by the youth, are publicly accessible on YouTube and reflect the themes they learned and expressed throughout the process.

Demo Day: A Community Finds its Voice

The project’s Demo Day marked a turning point for the entire community. Months of preparation went into the event. The center worked with local leaders, village executive officers, school representatives, and faith-based groups to ensure the gathering was open to everyone. Word spread through school assemblies, church announcements, and youth networks. By the time the day arrived, anticipation was high.

The community gathers at Mkapa Grounds for the project's Demo Day, captivated by youth performances and a powerful exhibition of their SRHR-themed art. Photo by Peter Salawe.

Held at Mkapa Grounds in Kisesa, the event drew 878 community members and more than 1,000 online viewers. Parents, teachers, religious leaders, health workers, and district officials sat side by side with students.

The youth marching to enter the Mkapa grounds during Demo Day. Photo by Peter Salawe, AICT Bujora.

For many, this was the first time they watched adolescents speak openly about consent, respect, and healthy choices. The stage became a meeting point for generations who rarely discuss these issues together. Performances by the finalists brought the crowd to life. Some songs carried humour, others emotion, and all carried lessons drawn from the participants’ own stories.

On stage at the Mkapa Grounds Demo Day, youth performers transform into health advocates, singing original lyrics about consent and prevention to an audience of hundreds. Photo by Makongoro Church Channel.

The artwork exhibition drew steady crowds as young artists explained the meaning behind their drawings: pressure from older partners, confusing expectations in relationships, and the struggle to make informed decisions without guidance.

Artwork displayed during Demo Day showing a headmaster sending a pregnant student away from school, reflecting past policies that forced girls to drop out. Today, Tanzanian girls are allowed to return to school after giving birth, marking a significant shift in national education policy.

Artwork by Baraka showing a girl receiving a gift from a man, unaware of the hidden risks behind the gesture. Drawing by Baraka, AICT Bujora.

What stood out most was the shift in adult attitudes. Parents who once avoided SRHR conversations found themselves clapping, asking questions, and congratulating the performers. Religious and local leaders, initially cautious, saw the value of the messages when presented through music, drama, and art. Several leaders afterward, invited the group to perform in churches, youth fellowships, and community meetings; spaces where such topics were rarely, if ever, allowed before.

Child and Youth Development workers in Mwanza Cluster pose for a group photo with the Guest of Honor, the Compassion Lake Zone Manager, the Auxiliary Bishop of the AICT Diocese of Mwanza, district officers, and other invited guests.

The gathering showed something important: when young people lead the conversation through creativity, adults listen differently. The event turned what could have been a one-time performance into an ongoing community movement. Demo Day also marked the beginning of long-term follow-up work, as schools and centers committed to continuing youth-led discussions after the event. Fifteen peer-led “Kijana Jitambue Sasa” clubs were inaugurated as a commitment to keep the conversation alive after the project. Once the celebrations ended, the clubs began meeting in the weeks that followed.

Magu District Chief Doctor inaugurating the 15 new youth clubs, marking a new phase of peer-led SRHR advocacy. Photo by Makongoro Church Channel

Reaching Beyond Bujora: Six More Centers Join in The Movement

The energy did not stop at one center. After the Demoday, the project expanded to six additional Child and Youth Development Centers (CYDCs) across the Mwanza Cluster: TAG Igogo, ELCT Bugando, EAGT Buzuruga, Baptist Nyamanoro, AICT Ilemela, and SEIC Lumala. They provide education support, mentoring, and life-skills programs for children and youth, particularly those from low-income backgrounds. These centers are deeply rooted in their communities and serve as trusted hubs where families, schools, and local leaders interact with young people daily.

SRHR educator sparks a candid conversation with attentive students at the SEIC Lumala Center, breaking down complex topics with clarity and compassion. Photo by Peter Salawe.

Youth gather for a Kijana Jitambue Sasa session at ELCT Bugando, continuing discussions sparked during the project. Photo by Philipo Florian.

At each site, SRHR educators and the trained youth ambassadors led discussions, performed the songs created during the project, and displayed the artwork. These sessions reached students who had not been able to attend the earlier stages of the program and helped inspire new conversations about rights, relationships, and personal responsibility. The outreach was not a short event. It grew into something more lasting.

Sustainability: Fifteen Youth Clubs Take The Lead

From this expansion, 15 peer-led “Kijana Jitambue Sasa” clubs were formally established across the CYDCs in the Mwanza Cluster after being inaugurated during the Demo Day, turning the project’s momentum into a long-term structure for learning and support. These clubs became the project’s long-term structure for sustainability.

Each club meets regularly; weekly, and is run by youth leaders and staff from the local churches. They follow official government-approved materials such as Kiongozi cha Mwezeshaji wa Stadi za Maisha, Mafunzo ya Afya ya Uzazi and the Reach Life (Fikia Maisha) book, designed to guide discussions on life skills, sexual health, faith, decision-making, and personal development.

The youth lead their discussion during the Kijana Jitambue Clubs meeting. Parents are invited also to listen to youth and give their inputs. The photo by Peter Salawe.

These clubs do more than continue the conversation. They create safe, structured spaces where adolescents can meet, pray, reflect, and talk openly about challenges they face. Members discuss sexual and reproductive health, relationships, self-esteem, life planning, and personal goals. Each club elects its own leadership and follows a clear guideline, allowing young people to learn responsibility and lead their peers.

Every three months, representatives from all clubs gather at the cluster level for a joint learning session. These meetings help reinforce accuracy, provide mentorship, and ensure the message stays aligned with national guidelines and community values.

This long-term integration is what gives the project its sustainability. Instead of ending when the music stopped or the art exhibition closed, the learning became woven into existing community structures. Youth are now leading discussions in spaces that will continue long after the project cycle ends. It means the movement no longer depends on one event or one center, but grows through young people who carry the message forward in their own communities.

Challenges Along the Way: Shifting Norms Takes Time

Change rarely moves in a straight line, and this project was no exception. Several schools hesitated when the team first requested permission to run SRHR sessions. Administrators worried about community backlash, especially in areas where discussions about sexuality are often mistaken for encouragement of early relationships. A number of parents also expressed concern, fearing that open conversation would disrupt traditional expectations of modesty.

The team responded by organizing meetings with village elders, religious leaders, teachers, and parent committees. They walked through the curriculum, explained the age-appropriate framing, and demonstrated how creativity was used to guide learning rather than sensationalize it. Once communities saw the clarity and sensitivity of the content, resistance began to shift.

At the Bulabo cultural event in Kisesa, the team used their booth to introduce the project and hear directly from parents and community members. The Kijana Jitambue Sasa banner is visible at the centre of the outreach space. Photo by Philipo Florian, AICT Bujora.

“We learned that transparency builds trust. By involving parents early, we turned critics into allies” says Jema, an SRHR instructor.

The Bigger Picture

These local challenges mirrored the broader national picture. Tanzania’s National Adolescent Health and Development Strategy (2021–2025) notes similar barriers across the country: limited teacher training in SRHR, hesitation among school authorities, and persistent community fears that talking about sexual health encourages immorality. The strategy points out that less than half of teachers feel equipped to teach SRHR, and youth-friendly services remain scarce in many districts, especially in rural areas. This alignment showed the AICT Bujora team that they were not facing an isolated issue; they were working within a national struggle to make accurate information accessible and acceptable.

Logistical challenges were just as demanding. Reaching scattered schools required reliable transport that stretched the project’s limited budget. Large school assemblies needed a functioning PA system. Producing brochures, booklets, and creative materials required both funding and time. Each obstacle slowed the pace of outreach.

This is where Compassion International Tanzania played a critical role. As a national child-development organization supporting more than 500 centers across the country, Compassion provides technical guidance, training, and funding for programs focused on education, protection, and youth leadership. Through financial support, printing assistance, and coordination with partner centers, Compassion helped the team cover transport, materials, audio and video production and equipment needs. They also offered guidance on safeguarding policies and adolescent engagement, ensuring that the project met national and organizational standards.

The partnership turned difficulty into momentum. What could have stalled the project instead became an opportunity to strengthen community trust, sharpen planning, and align the work with national efforts to reach adolescents responsibly and respectfully. The process revealed an important truth: meaningful SRHR education in Tanzania requires patience, partnership, and persistence; from the local classroom all the way up to national policy.

Evelyne’s Transformation: From Silence to Purpose

The project gave Evelyne more than skills; it gave her dignity, visibility, and a voice.

“Before the project, I didn’t believe my voice mattered. Now, I know I can use my talent to educate others” she says.

The project gave Evelyne a taste of a world she had only seen from afar. During the bootcamp, she stayed in a hotel for the first time and recorded music along the calm shores of Lake Victoria. For a young woman from a family that struggled to meet basic needs, stepping into a hotel once felt unattainable. That moment was not about comfort. It was about possibility. It showed her how far passion and purpose could take her and how creativity creates openings that circumstances alone cannot block. She now hopes to build a path in community health advocacy, with music as the center of her work.

With the waves of Lake Victoria as her backdrop, youth participant Evelyne records a song about sexual health, transforming the serene Igombe Beach into a studio for empowerment. Photo by Philipo Florian.

Evelyne’s experience speaks to something larger. Safe spaces do more than protect young people; they allow them to understand the social forces shaping their lives and their place within those forces. In the bootcamp, participants discussed pressures from peers, expectations from families, and fears about judgment. They learned how each of these dynamics influences choices around relationships, health, and identity. When young people are given room to explore these issues without shame, they begin to see themselves as part of the solution rather than silent observers.

Other participants shared similar shifts. Some said the bootcamp was the first time they spoke openly about relationships or asked questions they had carried for years. Others found confidence in seeing their drawings or lyrics taken seriously by adults. A few noted that working in teams helped them understand that change is not an individual effort, but something built through shared ideas and collective courage.

Together, these experiences demonstrated the value of spaces where adolescents feel heard, respected, and free to question. The project showed that when young people are trusted to analyze the world around them and express what they see, they gain the tools to influence their communities. They learn that they are not only recipients of information but active contributors to a healthier, more open environment for their peers. Safe spaces didn’t protect them from reality. They prepared them to face it.

The Model for Change: Why this Matters for Tanzania and Beyond

The Kijana Jitambue Sasa Challenge showed that transformation begins when young people are heard and trusted to lead. The songs, drawings, and new confidence reflect a wider movement. In a region where early pregnancy, low SRHR knowledge, and silence often intersect, the ability for youth to speak clearly and safely about their health is not a small achievement. It is a social shift.

The drawing showing the girls at the clinic getting the correct information on SRHR from the doctor. Kijana Jitambue Sasa Project.

Tanzania’s vision for reducing early pregnancy, HIV risk, and gender-based violence depends on youth who understand their rights, communicate responsibly, and challenge harmful norms calmly and confidently. When adolescents know how to navigate relationships with dignity and clarity, they are more likely to stay in school, avoid exploitation, and contribute to the their and their country’s development goals.

Across Mwanza, the project’s echoes continue: youth performing in schools, churches allowing discussions once avoided, parents listening, leaders engaging. It proved that sustainable SRHR education does not arrive through fear or shame. It begins with creativity, open dialogue, and young people who refuse to stay silent.