Entrepreneurship is an essential driver of societal health and wealth. It is also a formidable engine of economic growth. It promotes the essential innovation required not only to exploit new opportunities, promote productivity, and create employment, but to also address some of society’s greatest challenges, such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) or the economic shock wave created by the COVID-19/Coronavirus pandemic.

Business owners and aspiring entrepreneurs are often at the mercy of macroeconomic factors. When the COVID-19 crisis started, lockdowns reduced the revenues of existing firms and cash flow turned negative for companies that could not cut operating costs. The pandemic also threatened the potential for innovation, as access to capital and revenue became scarce for business startups.

In the face of the pandemic, Sudanese authorities acted quickly to slow the spreading virus. Since March 2020, Sudan, much like the rest of the world, has been experiencing the unprecedented social and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Businesses in Khartoum were forced to close due to a government lockdown. Source BBC/ Getty Images

Losses and Economic Fragility in Sudan

The main producer of official and reliable statistics in Sudan, the Central Bureau of Statistics and the coordinator of the National Statistics System that is responsible for organizing the statistical framework for the NSS to guide and inform policy formulation, planning, and decision making processes, conducted a High Frequency Survey in partnership with the World Bank. The survey assessed the impact of COVID-19 on Sudanese households and enterprises.

The findings of the survey on nearly 500 enterprises, representing the three districts of Khartoum State (Khartoum, Bahri, and Omdurman), highlighted the effects of COVID-19 on Sudanese enterprises and revealed both the losses and financial fragility of medium, small and micro enterprises.

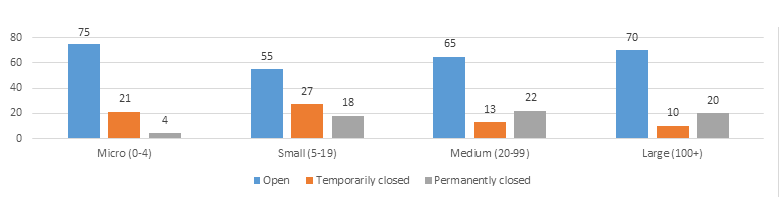

Of the surveyed enterprises, 29% had to close during the partial lockdown (8% permanently and 21% temporarily). Small enterprises (5–19 employees) were the most affected by the partial lockdown with nearly half of them going out of business. These enterprises did not have any savings or cash on hand to meet their regular expenses, which explains why layoffs were so prevalent. In contrast, around one-third of medium (20–99 employees) and large (100 and more employees) enterprises closed. Only one-quarter of the micro firms (0–4 employees) had to close.

Disruption to operations by enterprise size. Source: World Bank

The survey results also signified key financial problems perceived by enterprises as top obstacles to their operation; it included meeting staff wages and social security charges, paying rent and invoices, repaying loans, and accessing banking services.

The most significant financial problems for the enterprises in Sudan during the COVID-19 outbreak. Source: World Bank

The National Legislative Framework must Support Entrepreneurship

The formal private sector in Sudan is characterized by Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) and a few large companies, many of which are state-owned. MSMEs account for most private business activity in Sudan, and the few large companies that exist are clustered in trade and industrial processing areas and mostly located in Khartoum state, as few other places in the country offer the necessary infrastructure for large-scale commercial activities.

Despite the potential of MSMEs in terms of their contribution to GDP and employment, they face several constraints and there is a notable decline in private investments. These constraints are related to political instability and international isolation, macroeconomic conditions, business climate, and regulatory framework, as well as structural and sector-specific constraints. The COVID-19 pandemic further compounded the constraints faced by the sector.

The economic landscape during the pandemic further deteriorated as fear mongering increased the already existing greed, as some business people and entities people hoarded goods, especially sanitary products and food items. Lease agreements for small businesses were illegally tripled leading to forced closure and unemployment due to layoffs.

A woman erects a stall to sell her merchandise opposite a Bank of Khartoum branch. Source: https://www.cio.com/

This exposed another underlying issue that relates to economic laws. Sudan's national legislative framework surrounding Economic Social and Cultural Rights (ESCR) is weak in ensuring social protection for the populace to be able to assert an entitlement to any legal rights. In view of the adverse consequences of COVID-19, it becomes urgent to assess Sudan's social protection and social security legislation.

This includes the right to work and employment, labor-related laws such as the Labor Act (1997), Trade Unions Act (2010), Domestic Servants Act (1955), and other legislation regulating both the private and informal sectors, the Social Insurance Act (1999, as amended in 2004 and 2008), the Social Insurance and Pension Act (2016) and the Health Insurance Act (2016) with its limited coverage.

These laws provide some relevant regulation but are deficient, not least because they are not specifically tailored toward ensuring ESCR protection. The social insurance and social security laws do not envisage social protection for workers, including workers in the informal economy. A huge number of people in the informal economy are covered by neither the Labor Act nor the Social Insurance Act.

However, as many small businesses closed, some of the pandemic victims decided not to go down, dusted themselves and innovatively started some small businesses to help them earn a living during the hard times. Wawsi Village Society is an illustration of fighting against all odds to recover from disasters.

“We were hit and displaced by floods in 2019. Most of us lost all property and we relocated to an area that had no houses, bathrooms, or anything to start from. As we were still recovering, COVID-19 cases started being reported, followed by a mandatory lockdown” – Wawsi Village Society members during an interview with Andariya.

A member of Wawsi Village Society during an interview with Andariya. Source: Andariya

In an interview with Andariya, the group revealed that in 2021, they breathed a sigh of relief after a project by the International Organization for Migration and HOPE targeted over 50 women in Wawsi and trained them in sewing masks, making sanitizers and soap.

The project was a game changer and came at the most opportune time when there was high demand for the products, as almost everyone was taking precautions to keep safe. It enabled them to access a new source of income.

Revamping the Way Entrepreneurs can Adapt Post-pandemic

Only 15% of Sudanese adults have a bank account, yet 60% of the population are under 24, a youthful demographic that is increasingly tech-savvy. The mobile penetration rate is 76%, above the Middle East and North Africa's average of 64%, and it is increasingly clear that digitalization can bridge the gap in bringing banking services to consumers as payment apps and mobile wallets have far greater reach than traditional banks.

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the trend of going cashless, a trend that is particularly impactful in Sudan, where shortages of banknotes are not uncommon. This rise in fintech has altered the landscape of entrepreneurial pursuits.

The future of banking is digital. Source: Farmer’s Commercial Bank

With a population of close to 45 million, Sudan is one of the ten most populous countries in Africa, with tremendous economic potential. It has abundant natural resources, including oil and gold, a tenth of the world’s unused arable land, and access to the rapidly growing markets in Africa.

The Government of Sudan has put the modernization of the financial system at the heart of its agenda. Floating the Sudanese pound in February 2021, drawing $500 million into the formal system in just four weeks; a crucial move in securing much-needed debt relief and underpinning investor confidence.

Moving from cash to responsible digital payments is central to this broader economic and social agenda. In June 2021, Sudan joined the United Nation’s Better Than Cash Alliance, which will support its efforts to increase financial inclusion and digitalization, including the establishment of a Digital Transformation Agency.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the defects of the economic system as a whole, which has ignited a debate on the urgent need to revise the legal framework in order to better equip entrepreneurs with the technical capacity and easy-to-access revenue to withstand economic shocks.

The promotion of entrepreneurship will be central for the government for the foreseeable future, especially considering the significant negative impacts on economies due to the pandemic. Government and other stakeholders will increasingly need hard, robust, and credible data to make key decisions that stimulate sustainable forms of entrepreneurship and promote healthy entrepreneurial ecosystems worldwide.

The latest round of the Entrepreneurship Database gives a first snapshot of the relationship between business creation and the recent COVID-19 crisis. Future editions of the Entrepreneurship Database could shed light on the pace of recovery in new business registrations following the crisis. One key element is access to digital technology, which can strengthen the path to recovery and unleash the potential of aspiring entrepreneurs.