This article was originally published in African Feminism .

I always admired the younger generation, the late millennials and Gen Z youth who, time and again, showed us they do not subscribe to limiting societal values. They ask questions and do what they want either way. The women of these generations and the ones before them battled a grueling traditional mindset; that they were inferior, didn’t have choices and could not be trusted.

From birth, girls are told they have no power, that they should blend in and not make a ruckus, be good at school, not ‘open their legs’ before marriage and whenever possible just disappear. To see college girls, 16 -20 years old walking around wearing whatever fashionable clothes they want or mixing with male age mates openly in a country that judges women based on whether they’re home before sunset and how loose their clothes are, gives me joy.

It made me feel that women are here and must be trusted, they don’t have to be invisible, they can look violence in the eye, endure the humiliation and still come out the next round, respected and appreciated. All this, we witnessed in the early protests phase of the peaceful revolution. When the protests transitioned into an open sit-in at the army headquarters in Khartoum and other army sites across the country, the stark difference in gender representation in the next phases became sharply visible, creating a large rift between women on the forefront of this struggle.

Source: knowyourmeme.com

Then and Now

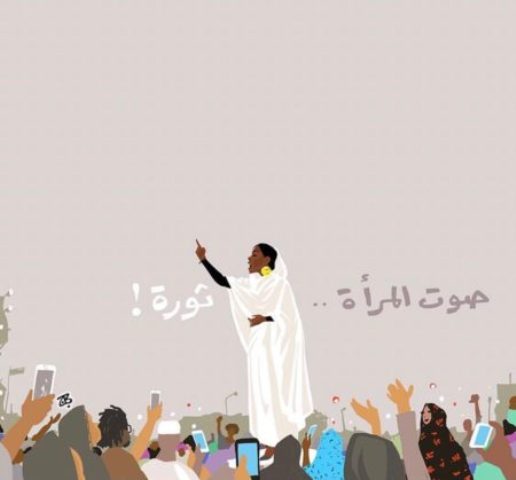

You now must know the iconic image of 22 year old Alaa Salah that was taken on April 8 2019 and made international headlines. In the famous viral photo, Alaa stood, beautifully clad in the working class outfit of white-toub and gamar boba earrings, chanting on top of a parked car to the enormous crowds at the sit-in, in front of the armed forces headquarters in Khartoum. Alaa represented female joy, a victorious young woman who found herself above the crowd, tantalizing them with patriotic poems while they roared chants, mesmerized and in awe.

Although numerous videos and photos circulated of the sit-in and protests before it, this one captivated the world for its representation of youth, women, culture, leadership and patriotism –a cocktail, the world drools over for revolutions are mostly bloody and brutal.

Before that photo, images of women protesting across Sudan, their faces covered with surgical masks, donning a hijab or not, wearing toabs, skirts, pants and abayas dominated protests coverage. Articles about women’s participation in the revolution between December and June were numerous. They depicted the artful representations as well as the challenges of convincing the family to allow them to engage, enduring the violence and rape-laced threats from the national security agents who detained them from the protests.

Then April 11th came, deposing of former president Omar al Bashir from power, by the will of the people who protested and marched relentlessly. It was executed by Bashir’s very own loyalist military strongmen, in a hoax to gain power through a transitional military council (TMC). Since then, the TMC oversaw the killing of more than 100 people and left as much as 700 injured in attacks on the sit-in, where paramilitaries reportedly carried out more than 70 rapes.

This was despite the negotiations between the TMC and de facto leader of the revolution, the Sudanese Professionals Association, and the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) which comprised several political factions and armed rebels under the Freedom and Change Declaration.

The pictures that came out of the negotiation meetings were starkly different from those that carried the news of the revolution months prior to that moment. What was evident was the lack of trust in the competence and capabilities of women in politics. This became clear as the negotiating team was selected despite the criticism. A total of 8 negotiators were selected, of these only one woman took part.

Social media was rife with angry comments about the dismal state of gender representation. Voices expressed that women have been exploited and left out in the foyer after deadly protests became closed meetings in air-conditioned halls. Yet the noise wasn’t loud or expansive across all segments; men, women, youth, activists, political leaders, journalists and civil society. Outside of our echo chambers, the status quo was embraced.

www.tumblr.com

The political sphere is eons behind the streets

Sudan is still a society that trusts older men, even though this revolution was delivered on the shoulders of teens and youth in their twenties, and their blood has been spilled. Women’s empowerment and access to education, formal and informal work hasn’t been effective in Sudan. Empowerment isn’t a physical or literal concept; such as enabling women to go to schools and universities, to provide employment and wage labor but rather it is a state of mind that women and men embrace to enable a wider effect. “Power” begins in the mind, when a female builds her confidence through reassurances by society signaling faith in her knowledge, choices, skills and intelligence. This must be aided by an environment of trust that measures competency based on real work, not gender.

When bomban man (a guy who throws back the teargas canister to the armed policemen) was celebrated, bomban woman was also celebrated. When women descended in droves to the protests and were called Kandakas, a powerful Nubian queen warrior, the flirtatious title pointed to the strength and ability of the women to show up, go through the same pains and come back up stronger and more resilient.

Although we have leadership in gender and political discourses, we don’t have effective representation, especially in the opposition. The leadership that exists navigates small circles and remains unknown to many who cannot see their contributions or qualifications as they have long been sidelined by the previous government.

On the economic front, walk into any institution, whether public or private, small or big and you’ll see many professional women in management positions. Due to the mass-migration of men aged 25-55 as a result of the pathetic economic situation that has plagued Sudan for almost a decade, women rose to the occasion. Yet in economics, just like politics, women in top positions are still rare.

Another problem is the slow uptake of the younger generation by the political movement. The movement could have identified movers and shakers during the protests and sit-ins and brought them into the team. Ignoring women leaders reflects daily challenges women face in most spheres. I’ve sat in meetings where I was the only woman in a power position, I’ve trained men who crossed their arms and cocked their heads in clear discomfort of my expertise. There’s a ‘secretary-syndrome’ most men want to enforce on smart, educated and opinionated women to shut them down.

While this is not a Sudan-only problem, at this crucial transitional and transformative time in our history, we need to quickly move to challenge such detrimental road-blocks. In a country where we are conditioned to observe the rich ‘solve’ the problems of the poor, educated those of the illiterate, dominant tribes ‘solve’ problems of the minorities and of course, men ‘solve’ women’s problems, this is the time to turn the tide, to infuse gender justice in the current emerging political bodies.

More than anything, women now need to be loud and establish connections with their community allies in our fight towards an inclusive and egalitarian society across all levels. Do we want to be leaders or do we want to be led? Do we believe we have what it takes to change society’s constrictive view of us? It isn’t easy, it isn’t cheap, but it sure as hell is worth it.

Inspired by Engaging Empowerment by Srilatha Batliwala.

“The neo-liberal rules for the new woman citizen…are quite clear: improve your household’s economic conditions, participate in local community development (if you have time), help build and run local (apolitical) institutions like the self-help group; by then, you should have no political or physical energy left to challenge this paradigm”. – Gender Myths that Instrumentalise Women by Srilatha Batliwala and Deepa Dhanraj.